Elizabeth Kolbert’s latest New Yorker article on the present era of mass extinction reads like a detective novel with a healthy dash of gothic horror thrown in. Unfortunately, it’s behind the pay wall, so I’m going to have to do my best to summarize a long and intricate story.

The cause and nature of extinction has been hotly debated since at least the time Charles Darwin put to rest the notion that species are fixed and eternal. Already in the 1800s, sudden changes in the fossil record seemed to suggest that cataclysmic events could abruptly rewrite the biosphere. Darwin himself rejected this notion. To him, the reliance on cataclysm to explain the fossil record represented a lazy way to sidestep our own ignorance of prehistory. Instead, he supposed that extinction was the mirror image of evolution, an imperceptibly gradual process arising from steady and subtle competition between species.

Darwin was wrong, but his theory held sway until 1980, when it was exploded in dramatic fashion by a six-mile wide asteroid. The asteroid in question fell to earth 65 million years ago, wiping out all of the dinosaurs and the majority of other species on the planet. Although waves of extinctions have happened numerous times in the past, the dinosaur-killing asteroid triggered the last of what are known as the Big Five extinction events.

Scientists think we may now be in the midst of a sixth major extinction. Fifty thousand years ago, Australia lost its large animals, which included ten-foot-tall kangaroos and car-sized tortoises. Eleven thousand years ago, North America shed most of its large animals, including mastodons, sabre-toothed tigers, and giant beavers. Soon South America followed suit, losing its elephant-sized sloths and other megamammals. 1,500 years ago, Hawaii lost 90% of its bird species.

Much more recently, scientists noticed waves of frog deaths spreading across central America. Oddly, at the same time that frogs were dying in Panama, the same species of frogs were inexplicably dying in North American zoos.

Although the extinctions have varying causes, they spread by a common mechanism: humans. The disappearance of the large mammals and marsupials seems to be a simple case of resource competition. The death of Hawaii’s birds probably owes more to the invader species — particular rats — that piggyback on humankind’s travels.

The frog story is similar, but far weirder. In the 1930s, a type of amphibian known as the African clawed frog was discovered to lay eggs when exposed to certain human hormones. In short order, African clawed frogs were transported all over the world for use as a pregnancy test. In the ’40s and ’50s obstetricians kept tanks of them in their offices. The frogs carried with them a fungus that eventually escaped into the water supply, triggering the wavelike extinctions that biologists noticed several decades later.

Something similar appears to be happening now to North American bats, although the exact mechanism has yet to be determined. The article’s bit of gothic horror comes in the form of a trip to a cave in Vermont that turns up piles of decomposing bats — extinction in action.

Species are resilient. Bats, frogs, and sabre-toothed tigers all managed to survive and thrive through several ice ages and other dramatic environmental events. What makes contact with humankind so uniquely threatening? The answer appears to lie with the pace of change. The biosphere bends until it breaks; die-offs can be startlingly sudden.

Which, of course, brings us to climate change. Interestingly, an abrupt increase in carbon dioxide levels might have played a role in the third mass extinction, known as the Permian or the Great Dying, which occurred 250 million years ago. Sudden swings in carbon levels trigger all sorts of now-familiar effects, including ocean acidification, increased temperatures, and altered weather patterns. The Permian happens to be the worst of the previous big extinctions. Of course, these events can only be judged in hindsight. It will be a long time before we know how the present one plays out.

(Although the New Yorker article itself is inaccessible, you can hear an interesting related podcast interview with the author here.)

Brought to you by terrapass.com

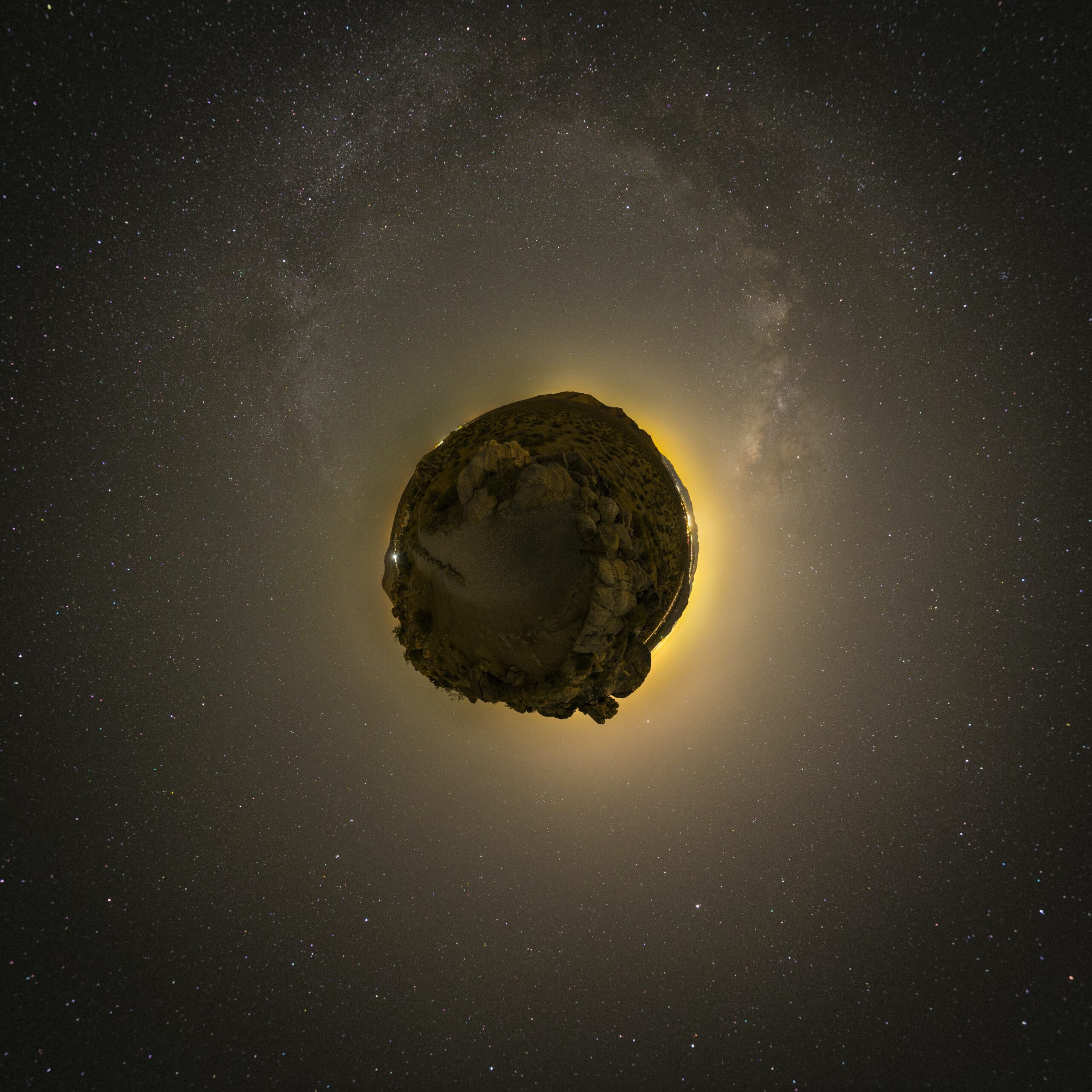

Featured image